This Old Book

Eric D. Lehman

is a Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut and has previously published reviews, essays, fiction, and poetry in journals such as Red River Review, Magnolia, Entelechy, Switchback, and here at Umbrella. —Back to Orsorum Contents/Issue Links— |

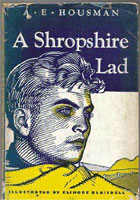

A Shropshire Lad by A.E. Housmanby Eric D. Lehman

R eading A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad is one of those experiences in which reality matches the legend. At first rejected by publishers, Housman was forced to use his own money to print these anecdotes of lost friends and tragic lovers. When the Boer War and later World War I took the lives of so many young Brits, the book, so charged with loss and longing, became a classic. Later still, the solemn subject matter and nearly uniform style left Housman open for easy parody, and thus the book faded from popular opinion. Though a few poems remain canonical, Shropshire’s genuine yearning for the personal past is something the cynical and self-referential poetry critics of the twentieth century often laughed at. However, when we pick up this volume expecting outdated 19th century rhyming and narrative excess, we cannot help but be surprised. The language appears tight and focused, the rhymes not clunky but subtle. We might also be surprised by Housman’s consistent sense of sound. Lines like “White in the moon the long road lies” tremble with alliteration and assonance. His use of 8-6-8-6 stanzas produces a songlike quality in the poems, and focuses our attention on the precise wording. Phrases like “how thick the goldcup flowers” and “like the wind through woods in riot” could be considered precious, but thrive within a larger context of narrative and linguistic simplicity Along with well-known poems like “Loveliest of trees, the cherry now,” and “To an athlete dying young,” Housman packed this slim volume with lesser known beauties that tell simple stories in few words.

When I came last to Ludlow The scenario of this poem speaks of the transient nature of human lives, while the repetition in the first and last lines reminds us that those lives exist within the eternal framework of natural cycles. It is Housman’s ability to combine deeply felt philosophy with genial language that remains a source of interest, even while modern readers’ taste for “rhyming poetry” seems to wane. Many of the poems in A Shropshire Lad deal with a number of universal, perpetual principles. But the one theme that continues to resonate with modern readers speaks to our nostalgia for the past, for the uncapturable beauty of our childhood. Housman writes:

Into my heart an air that kills At first the choice of “kills” seems odd, but Housman is only taking strong emotion to its logical conclusion. The “air” or music of the past will lure us away from the present moment, and thus to our doom. He continues:

That is the land of lost content, The reader immediately realizes that all the poems in this collection are missives from that land of lost content. Poems like “With rue my heart is laden” seem to mourn for the “lightfoot lads” and “rose-lipt maidens” that are now dead and gone. But these lads and maidens, though real enough, are also reflections of our own mortality. In poem XX, he tells us of a wish to dive into the pools and rivers of the past, which “wash so clean” the world we live in. He ends with “But in the golden-sanded brooks/And azure meres I spy/A silly lad that longs and looks/And wishes he were I.” The wisdom of Housman’s verse is apparent here. Of course every child trades away paradise in the hope of something better. But though this collection seems to pine for a lost innocence, Housman counters that feeling with a rueful acceptance. He knows that events always appear brighter when looking over our shoulders, and the past is little more than a wishful illusion.  Eric D. Lehman is a Professor of English at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut.He has previously published essays, fiction, and poetry in various online and print journals, such as The New Formalist, Red River Review, Switchback, Venture Magazine, and Entelechy: Mind and Culture. Eric D. Lehman is a Professor of English at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut.He has previously published essays, fiction, and poetry in various online and print journals, such as The New Formalist, Red River Review, Switchback, Venture Magazine, and Entelechy: Mind and Culture.

| ||

|

|

|||